A Psychological Analysis from a New Biography of former South African President Thabo Mbeki

By Qi Xie

“I didn’t want to write a hagiography,” said author Dr. Adekeye Adebajo at the book signing event for his new biography of Thabo Mbeki, South Africa’s second post-apartheid president, held at the New York headquarters of the noted think tank, the International Peace Institute (IPI). Indeed, Adebajo’s account of Mbeki’s life does not idealize, but rather exposes highlights and also the underbelly of the politician credited for overseeing a growing economy and black middle class, the formation of the African Union, and positioning South Africa as a regional power, but ultimately being forced to resign. While Adejabo defended his labeling Mbeki as Africa’s philosopher-king – a term referring to the Platonic ideal of a ruler who is philosophically trained and enlightened – he was adamant to say that he wanted to avoid the tendency of intellectuals to fawn over prominent political figure.

Adejabo, currently the Executive Director of the Centre for Conflict Resolution in Cape Town, the continent’s leading think tank on peace and security issues, said that he wrote the book for three reasons: “to rescue Mbeki from the parochialism of South Africa and restore him to the Pan-African pantheon”; to emphasize that Mbeki’s legacy is more likely to be in the area of foreign rather than domestic policy; and to correct the absence of black authors as biographers of African political figures. Adebajo said at the event that he did not personally interview Mbeki for the book, but based his work on extensive research.

A Rhodes scholar who obtained his doctorate from Oxford University in England, Adebajo clearly knows about the history of Africa. He has authored several books, including The Curse of Berlin: Africa after the Cold War and UN Peacekeeping in Africa: From the Suez Crisis to the Sudan Conflicts; edited Africa’s Peacemakers: Nobel Peace Laureates of African Descent and From Global Apartheid to Global Village: Africa and the United Nations; and is a columnist for Business Day, a national daily newspaper in South Africa. He also previously served on United Nations missions in South Africa, Western Sahara, and Iraq, and as IPI’s Director of the Africa Programme, when he was also an adjunct professor at Columbia University's School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA).

The event moderator Ambassador John Hirsch, Senior Advisor of the International Peace Institute and discussant Ambassador Princeton L. Lyman, Senior Advisor of the United States Institute of Peace, clearly were knowledgeable about Africa, adding context to the life and times of the African leader, as did other distinguished attendees, including H.E. Ambassador Téte António, Permanent Advisor of the African Union to the UN. In the packed room were invited ambassadors, high level representatives of UN agencies, NGO representatives, journalists, academics, and other interested IPI associates.

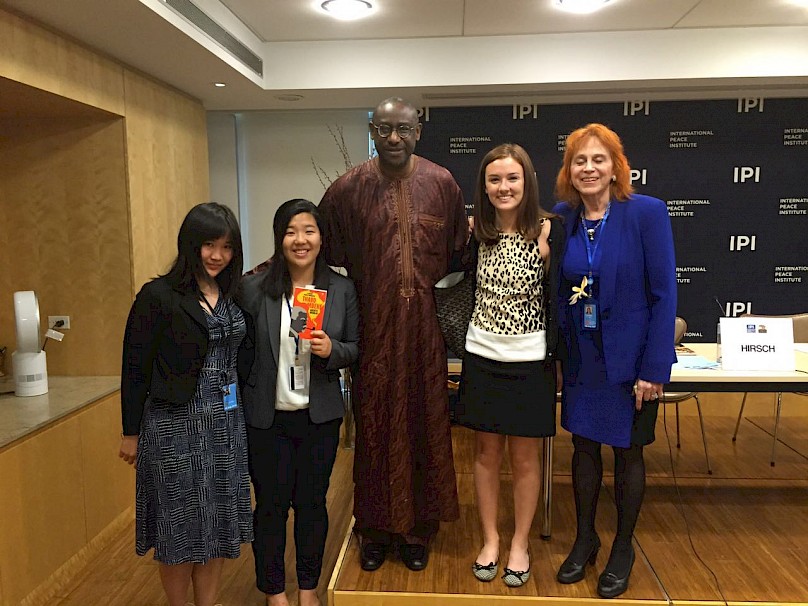

As a youth representative for the International Association of Applied Psychology, I was invited to the event by my supervisor Dr. Judy Kuriansky, who is a friend and colleague of Dr. Sathasivan ("Saths") Cooper, a South African psychologist who as a young anti-apartheid activist was imprisoned in the same cell block for several years with Nelson Mandela. Mandela was obviously a significant figure in Mbeki’s life and Adebajo’s book, as both were contemporary top leaders of South Africa and of the African National Congress (ANC), the anti-apartheid party that became the ruling political party of post-apartheid South Africa in 1994. I was keen to attend this event, since I also have strong interests in comparative politics, and was intrigued by Thabo Mbeki, who is eclipsed in fame by his predecessor Nelson Mandela and the currently ruling Jacob Zuma, but whom Adebajo called “the most important African political figure of his generation.” Further, I am fascinated with psychology, and Adebajo’s account of Mbeki was rich for analysis.

“As a political figure, Thabo Mbeki was a man of great complexity (p.75),” says Adebajo in his book. For me, the book presents a nuanced examination of the psychological contradictions that underlie Mbeki’s complicated legacy.

One of the ways that Adebajo sheds light on Mbeki’s idiosyncratic personality is, ironically, through comparisons with other prominent politicians past and present. These include founding President of Ghana Kwame Nkrumah, former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, and legendary Roman empire general Coriolanus, who all served as points of the author’s reference. Specifically, Mbeki shares with Nkrumah a tendency towards intellectualism, but lacks Nkrumah’s charisma. A self-proclaimed “Thatcherite,” (characterizing the conservatism of British politician Margaret Thatcher), Mbeki similarly sought to revive his country through neoliberal economic policies and an iron grip on power. Coriolanus was eventually brought down by his “obduracy and pride” (p.23) that closely parallels Mbeki’s own downfall, a fate (perhaps unsurprisingly) endured by all four leaders despite their diversity in culture and century.

As described in the book, Mbeki’s psychological makeup is complicated, intermingled with somewhat clichéd elements. His father’s “coldness and emotional reserve [and] lack of paternal affection” (p.28) contributed to the son’s “introverted and sensitive nature” (p. 28), yet the elder Mbeki’s example of obsession with success drove the son to prove himself intellectually and politically. In addition, eager to escape his father’s shadow, he was keen to succeed on his own terms; and in his father’s absence, adopted the political party as the substitute. On another psychodynamic dimension, his “short physique” would by any traditional psychoanalyst’s interpretation lead to “accusations of a Napoleon complex” (p.75), which means assuming a “larger than life” character to overcompensate for insecurity in his stature and nature.

Adebajo described Mbeki as a “nocturnal workaholic who survived on only a few hours’ sleep…famously surfing the internet late at night” (p.16) and also a micromanager who “insisted on appointing provincial premiers and top civil servants” (p.77). Unsurprisingly, the predisposition and ability to power through long days with minimal sleep (from what I’ve read) has been attributed to politicians and world leaders who reach top levels of control, including Napoleon, Thatcher, and Stalin.

Mbeki certainly accomplished a lot during his career. When the ANC was banned in South Africa, Mbeki went into exile in many countries, including Russia, Zambia, Botswana, Swaziland, Nigeria and Zimbabwe, but still was able to be actively engaged in ANC affairs. Years later, when serving as deputy president to Mandela, he took major responsibility for policy and its implementation. However, his positive political accomplishments were marred by inconsistencies. Namely, while he fostered a strong black identity through initiatives such as the Black Economic Empowerment (BEE), he was criticized for elitism and focusing too much on the middle class.

Even more distressing, recounts Adebajo, Mbeki’s notorious ban of antiretroviral drugs in public hospitals – and the worst “blemish on his record” (p. 105) -- is estimated to have caused up to 365,000 deaths that could have been prevented. This serious misjudgment, to claim that HIV is not the cause of AIDS, is said to have contributed in large part to his downfall. In my view, his intentions were certainly honorable - to “reject claims that AIDS originated in Africa and that it was spread by what was sometimes stereotypically depicted as uncontrolled black sexuality” (p.105) - but his actions were disastrous.

I cannot help but speculate that Mbeki’s personal and psychological roots contributed to his contradictory policy stances. His journey is one from a rural child to an urban sophisticate, and from an idealistic Marxist to a cunning Thatcherite. His African upbringing, Anglophone education (studying economics in England), and two decades of exile, seem destined to form his eclecticism, which could also underlie his apparent conflicted definition of Africanism. Mark Gevisser, another of Mbeki’s biographers, referenced in Adebajo’s own account, noted that Mbeki’s relationship to the “real Arica” is fraught with ambivalence, for “with every example he presents, it becomes clearer that even though he is attracted to it, it is antithetical to everything he stands for” (p.55).

In addition, he could be criticized for not strongly enough supporting “Africa for Africans,” evident in his comment, “The ANC’s approach is sometimes summarized as elements of a northern European approach to social development combined with elements of Asian approaches to economic growth…” It is this view that biographer Adebajo calls “the clearest sign of an inferiority complex” (p.89).

While in my view, having a complex character acquired through exposure to diverse experiences could serve one very well as a leader who respects all levels of society including the ones most behind, this was seemingly not the case for Mbeki. Adebajo quotes Mbeki’s admiration for Coriolanus ‘for being prepared to go to war against his own people, whom he described as ‘rabble … an unthinking mob, with its cowardice its lying, its ordinary people-ness” (p.24). This being “out of touch with his own citizens” (p. 110) eventually proved to be Mbeki’s undoing. Events unfolded on the South African political arena, says Adebajo, much like the storyline of the 1963 play, The Lion and The Jewel, by Nigerian Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka, where the westernized urbanite eventually loses out to the crafty traditional chief in their competition over the beautiful village girl. In real life, the populist Zuma, who has four wives and often wears traditional Zulu dress, ultimately “won the crown” of the South Africa presidency over the intellectual “philosopher-king” Mbeki.

Biographer Adebajo said at the IPI book launch that he wished neither to make an anti-intellectual nor an elitist argument concerning the desirability of political candidates. This statement, seeming to imply the upcoming American election, elicited a humorous reaction among the international audience assembled for the event.

Hearing Adebajo’s presentation and reading his book helped me understand a politician’s legacy in terms of his psychological and personal qualities and quirks. Such exploration is always an interesting enterprise, which I also found in viewing House of Cards, an award-winning TV series about ruthless power-mongering originally set in Britain and now on the internet, adapted for the US. The psychological intrigue, scheming, and power shifts are as much a draw for me as is Adebajo’s insightful new biography of Thabo Mbeki.

From left to right: IAAP Intern Qi Xie, IAAP Intern Janie Baek, Dr. Adekeye Adebajo, IAAP Intern Colleen Hanna, our supervisor Dr. Judy Kuriansky