Food Waste Mitigation: Achieving Sustainable Development, Well-being, and Hunger Eradication, Applying Behavior Science in the Model Case of South Korea, and Advancing COVID-19 Recovery

by Shelby A. Parks

Published June 2021

Food Waste Mitigation: Achieving Sustainable Development, Well-being, and Hunger Eradication, Applying Behavior Science in the Model Case of South Korea, and Advancing COVID-19 Recovery

On a global scale, humanity throws out approximately 1.3 billion tons of food a year, or one-third of all of the food that is grown (Sengupta, 2017). This presents an urgent problem, considering statistics that the world population is expected to grow to over 10 billion people by 2050, and that when coupled with the crises caused by climate change, agricultural production will need to expand by approximately 70 percent by 2050 to meet humanity’s basic food and fiber needs (“Water in Agriculture”, 2020).

The tragedy is clear: so much of the world population is hungry yet so much food is being discarded.

With more than a quarter of a billion people potentially at the brink of starvation (“Risk of hunger”, n.d.), swift action needs to be taken to provide food and humanitarian relief to the most at-risk regions.

Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The urgency for mitigating food waste is that much more evident in the times of the COVID-19 pandemic plaguing the world in the year 2020. According to the World Food Programme, 135 million people suffer from acute hunger largely due to man-made conflicts, climate change, and economic downturns (“2020 Global Report”, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic could now double that number, putting an additional 130 million people at risk of suffering acute hunger (“Goal 2”, n.d.).

The interrelationship between food, COVID-19, and stress is clear. According to researchers, people who report food insecurity are at an increased risk of mental illness, which is further exacerbated in high stress and isolated environments (Martin et al., 2016; Pourmotabbed et al., 2020).

These factors are creating a cyclical “perfect storm” whereby the pandemic is creating emotional trauma as well as food insecurity in terms of lack of access and affordability, while conditions of the food insecurity combined with isolation and fears caused by the pandemic, in turn, are causing stress, mental health and psychosocial problems (Kuriansky, 2021). At the same time, consistent with psychological theories of post-traumatic growth, this crisis also offers a rare opportunity for food systems transformation.

Context of the UN Global Agenda

The problem of food waste is intricately tied to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development, a framework that outlines a plan of action for the people, planet, and prosperity which governments of the world agreed upon in 2015 (“The 17 Goals”, n.d.). Food waste is particularly egregious given SDG 2 which calls for eradicating hunger (“Goal 2: Zero Hunger”, n.d.).

Importantly, a solution lies in Sustainable Goal 12, about sustainable consumption and production (“Goal 12: Responsible Consumption”, n.d). This goal is about promoting resource and energy efficiency, sustainable infrastructure, and providing access to basic services, green and decent jobs, and a better quality of life for all.

Food waste is also tied to SDG 13 about climate action, in that food waste which goes to landfills produces methane, a greenhouse gas even more potent than carbon dioxide (“Goal 13: Climate Action”, n.d.; “Fight Climate Change”, n.d.) Thus, to reduce global temperatures calls for a reduction in all greenhouse gases, including methane. As such, food waste is directly linked to food sources, referred to in SDG 14 about life below water and SDG 15 about life on land (“Goal 14: Life Below Water'', n.d; “Goal 15: Life On Land”; n.d).

In addition, the food waste issue and its relationship to the above-noted SDGs are interlinked with target 3.4. of the Agenda, namely, “to promote mental health and wellbeing”, since mental health and well-being are inherent in psychosocial and psychological principles which will be shown in this paper as solutions to the food waste crisis (“Sustainable Development Goals”, n.d.; Kuriansky, 2021).

This paper explores the issue of food waste as interlinked with those sustainable development goals, and solutions based on solid behavior science. Significantly, a government model solution to this problem evident in the approach of the country of South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is presented.

Overview of the Problem

Producing food that goes uneaten wastes a variety of both environmental and human resources, including land, soil, fertilizer, water, seeds, and energy, in addition to hours of labor (“Reducing the Impact”, 2020). Freshwater is one of Earth’s most precious resources, and 70 percent of it is used for agricultural purposes, including crop irrigation and drinking water for livestock (“Water in Agriculture”, 2020). As it pertains to SDG 14 which calls for conservation and sustainable use of the sea, the waste of freshwater through food waste and food loss depletes this already limited resource (“Oceans”, n.d.). Moreover, this level of waste extends beyond financial waste as each stage of the food production process generates greenhouse gases. As a result, this wasted food is responsible for approximately 8 percent of global emissions (“Emission Database”, 2012).

According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), if food waste were a country, it would be the third-largest greenhouse gas emitter (“Minimizing Food Waste”, UNEP). In a staggering example, in the United States alone, a large amount of the production of food is lost (“Fight Climate Change”, n.d.; Newman & Cepeda-Márquez, 2018). This lost food refers to food that inadvertently undergoes decay in quality or quantity due to food spoils or bruising as a result of infrastructure restrictions at the production, storage, processing, and distribution phases of the food lifecycle. Lost food is also wasted food, referring to any food and inedible parts of food that are removed from the food production process which can be recovered or disposed of. This lost food produces the equivalent of 37 million cars’ worth of greenhouse gas emissions.

To combat this growing crisis, humans need to find solutions to food waste, making it easier to redistribute waste and to meet the food needs of the growing population and the additional 2 billion people the world will be home to by 2050 as made clear by SDG 2 (“Goal 2, n.d.) Due to the magnitude of this issue, The World Economic Forum recognized reducing food waste up to twenty million tonnes as one of twelve actions that could help change global food systems by 2030 (United Nations, n.d.). These steps are supported by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, specifically SDG 12.3 “Food Waste Index” which calls for reducing the per capita global food waste by half at both the retail and consumer levels by 2030 (“SDG 12.3”, n.d).

Food Waste Versus Food Loss in High and Low-Income Countries

The global food waste issue exists both in high- and low-income countries, although with some differences. Generally, food is lost or wasted throughout the food chain within low-income countries during the early stages of the supply chain, due to limited harvesting techniques and storing facilities (Gustavsson et al., 2011). In contrast, high-income countries experience food waste further down the supply chain at the retailer and consumer level (Bravi et al., 2019; “Water in Agriculture”, 2020).

To quantify food waste in developed countries, approximately 40 percent of wasted food is thrown out by consumers (Gunders, 2012). This food waste at the consumer level in high-income countries is the result of several factors including people purchasing too much food, serving too much food during meals, and rejecting imperfect foods which have bumps and bruises.

Additionally, households with higher incomes are more likely than those in lower-income countries to waste more food. This is because food tends to be cheaper than other goods. This becomes increasingly evident in developed countries where the proportion of expenditure on food is low, relative to the total expenditure of each household (Pearson et al., 2013; Gunders, 2012). For example, a report from 2012 indicated that U.S. citizens spent only 6.1% of their income on food, in stark contrast to Pakistan, where citizens spent 47.7%, or nearly half of their income on food (Thyberg & Tonjes, 2016)

Ground-Level Solutions in Developing and Developed Countries

Fortunately, interventions can reduce food loss and food waste in developed countries to ensure sustainable food production systems and agricultural practices to maintain balanced ecosystems as set forth by SDG 2.4 (“Goal 2”, n.d.). Solutions also apply to developing countries.

In developing countries, recommendations by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) include encouraging farmers to collect vegetables in plastic crates instead of big sacks to reduce rotting and the chances of food becoming squished (Sengupta, 2017). Other interventions are being made to improve infrastructure, storage, processing, and transportation. For example, improved training in milk handling for dairy farmers has reduced product contamination and spoilage in addition to efficient refrigeration and cooling structures for dairy and meat products (Galford et al, 2020). Moreover, improvements in transportation between harvest and collection centers through the establishment of feeder roads have demonstrated reductions in food loss and food waste (Galford et al, 2020).

For developed countries, at the retail level in developed countries, supermarkets are playing a role in changing “best by” and “best before” labels to discourage consumers from throwing out food that is safe to eat, along with the development of companies that sell misshapen fruits and vegetables rather than discarding them (Gunders, 2012; Hingston & Noseworthy, 2020). Retailers are even donating food that is at risk of being thrown out but is still safe (Aschemann-Witzel et al., 2016)

Yet, these interventions have not reduced food waste enough in industrialized countries and major interventions through policies at the national level are needed to create this change (Aschemann-Witzel, 2015).

One government that has made substantial strides to reducing food waste is in South Korea, as described in the following section.

The Case of South Korea

South Korea is an outstanding example of a country’s approach to the food waste crisis. The success of their creative approach is evident in imagining a world where every scrap of food a person throws away would cost that person money. Or, one can imagine a world where, if you did not take home your leftovers after dining in a restaurant, you were charged five extra dollars on your bill. Similarly, imagine a world where the spoiled milk you forgot to drink before its due date costs you two dollars to discard.

South Korea is an outstanding example of a country’s approach to the food waste crisis. The success of their creative approach is evident in imagining a world where every scrap of food a person throws away would cost that person money. Or, one can imagine a world where, if you did not take home your leftovers after dining in a restaurant, you were charged five extra dollars on your bill. Similarly, imagine a world where the spoiled milk you forgot to drink before its due date costs you two dollars to discard.

For South Koreans, this world exists.

These principles are based on behavioral psychology, which will be further described below.

In 2013, the government of South Korea introduced a compulsory food waste recycling system that requires residents in the capital city of Seoul to discard food in special biodegradable bags and smart bins which weigh the food in the bags and then charge a fee for food waste (Broom, 2019). Since its inception, this pay-as-you-go system has reduced food waste in the city by 47,000 tons in six years, increasing the food waste recycled from 2% in 1995 to 95% today (Broom, 2019). The city is now home to 6,000 automated bins where people can weigh their food waste and pay their fees (Broom, 2019). Once the waste from the bins has been recycled, the waste is processed into biofuel or turned into fertilizer to help urban farms (Broom, 2019).

Incentive as a Means to Success through Behavior Science

This program has seen exponential success because it relies on incentives as a means for change. An incentive is something that motivates or encourages an individual to do something. As a clear principle of behavioral science and psychology, incentives are the reason why people do things (Hurlock, 1931). The incentive can be an internal desire, or, behaviors are driven by an external reward or avoidance of something undesirable (Kool et al., 2010).

This approach is similar to the principles of classic conditioning in psychology, whereby behavior leads to rewards or punishment. For example, you might run a marathon to be “rewarded” with losing weight, or a student finishes homework to avoid “punishment” of receiving a poor grade. Human behavior is influenced by an incentive to gain something, or to avoid something, as a result of effort (Kool et al., 2010).

Incentives play a large role in SDG 13, calling for climate action, which, as mentioned above, is interlinked with SDG 2 and the food waste problem. One of the biggest challenges humanity is facing in fighting climate change is the lack of a motivating incentive (Swim et al., 2011). As of today, the majority of the world can dispose of their garbage — that leads to greenhouse gases in the atmosphere — at no financial charge or cost to them in hard cash (Barclay & Irfan, 2019). This makes it difficult to motivate behavior change which would result in more sustainable and eco-friendly practices (Barclay & Irfan, 2019). In contrast, adding a real cost to emitting greenhouse gases can create extrinsic motivation to produce fewer greenhouse gases emitted from food waste which ends up in landfills, and to switch instead to alternative behavior and solutions which are safer for the environment (“Sustainable Management”, 2021). Moreover, this type of urgent action and methods to combat climate change is essential to meeting SDG 13 and adopting actions to keep global temperature rise to below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels (source).

The solution which South Korea has implemented builds on best practices in the psychological science of behavior change, by using incentives as a means of mitigating food waste. Charging a fee for food waste, as imposed in South Korea, taps into people’s motivation to avoid spending extra money. Putting a price on wasting food, and building on people’s motivation to avoid paying a fine leads to a constructive outcome, whereby people are driven to think about their relationship to food and what they are wasting. This approach can further motivate considerations about what they are eating. While the greater impact of food waste and the role it plays in climate change is considerable, the personal impact of imposing a personal financial cost creates a greater incentive at the individual level to reduce food waste (Swim et al., 2011).

Immediate Gratification

The value of South Korea’s food waste program is further supported by research that shows that reward – including in the form of money – matters in motivating care for the environment (Lombrozo, 2015). Rewards can be extrinsic or intrinsic. Intrinsic rewards are psychological rewards that one receives internally in the form of personal achievement, professional growth, or a sense of pleasure or accomplishment (“Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic”, 2019). Extrinsic motivation is based on tangible rewards, such as money, a trophy, or a prize. Research suggests that motivating sustainable behavior with an extrinsic reward could be more effective than intrinsic motivation to increase care for the environment (Lombrozo, 2015).

While people may be intrinsically motivated, humans are wired for immediate rewards – also known as immediate gratification in psychology terms – which are more extrinsic, especially as it pertains to climate change (Duhaime, 2017). Behavior experts have noted humans’ difficulty to perceive climate change as an immediate threat, which has consequently led to excessive consumption (Swim et al., 2011). Today, this overconsumption comes in the form of over-purchasing at the grocery store or ordering excessive amounts of food at a restaurant, similarly as for our ancestors, where overconsumption quite literally occurred in the form of over ingesting large amounts of food for various cultural and survival reasons (Duhaime, 2017).

The ancestral origins of food overconsumption and waste are relevant in present considerations of the problem. During early centuries, according to human evolutionary history, when food was scarce, the brain’s reward system was shaped to promote survival and reproduction; thus, humans would consume more than their immediate short-term caloric needs in case food was not available for a few days (Duhaime, 2017). While this level of consumption is unnecessary in developed countries today, the necessity to over-consume as a means for survival for our ancestors has generational roots that can be ingrained (Swim et al., 2011). This can help explain why we overconsume even when we don’t need to, which leads to the typical American behavior of throwing away 40% of their acquired or purchased food each year (Duhaime, 2017).

These principles lead to strategies about how to change people’s behavior regarding food. Due to this principle of people’s contemporary need to attain immediate tangible rewards, organizations have discovered that rather than teach didactically about sustainable consumption with factual information, a more effective approach is to build upon what people find rewarding that will drive them towards sustainable behavior (Duhaime, 2017). This understanding has important implications for educational systems about prosocial behavior that determines people’s intentions towards environmental protection (Nemeth, Hamilton & Kuriansky, 2015).

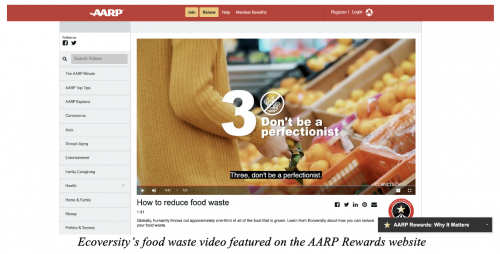

One company applying the immediate gratification approach to more sustainable behaviors around food waste is AARP, the largest nonprofit organization in the United States dedicated to empowering Americans who are 50 years and older. AARP’s loyalty gamification program, called AARP Rewards, is designed to help users through major life transitions. They incentivize learning by allowing users to engage with videos, quizzes, articles, and more so that they learn about a specific topic while also earning points for their engagement.

As part of their programming around Earth Day, the AARP Rewards team, through their Director of the Loyalty Program, Imani Joyce Samuels, partnered with the author of this paper, Ms. Shelby Parks, through her participation in the Ecoversity education program, on a campaign around food waste in honor of Earth Day to help AARP Rewards users understand tangible ways to engage in climate action. As part of this initiative, Ms. Parks developed a short video, “5 Tips to Reduce Food Waste”. AARP Rewards sent the video out to 850k newsletter recipients and hosted the video on their platform. AARP Rewards members were incentivized to watch the short video to earn 300 Rewards Points which they can then trade in for gift cards and other prizes.

The project was launched on April 20th, 2021, garnering 1.1 million newsletter impressions and 24,000 video views by the AARP Rewards program members. It was further publicized in a presentation at an event during the United Nations Commission on Population and Development by psychologist and United Nations NGO representative, Dr. Judy Kuriansky, professor of the course on “Psychology and the United Nations” which both Samuels and Parks took as part of their graduate studies at Columbia University Teachers College (Kuriansky, 2021).

The approach of psychological science and behavior is evident in the formulation of South Korea’s approach to mitigating food waste. Saving money provides the incentive to motivate people to not waste food. Therefore, while people may or may not be intrinsically motivated to reduce food waste to reduce greenhouse gases, or may not respond when they are lectured about the negative outcome of food waste, the government of South Korea successfully created an extrinsic motivation for positive sustainable food behavior through a monetary incentive. This approach demonstrates that creating an extrinsic incentive, such as money, as a reward for sustainable behaviors, can create positive change to mitigate food waste and create sustainable consumption, thereby helping achieve the UN Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development.

Conclusion

Food waste is an increasing global problem, impacting several of the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations Agenda 2030, including SDG 2, 11, 13, 14, and 15 as well as target 3.4 about mental health and well-being. Solutions are based on changing people’s behavior, which refers to psychological principles of behavior science and behavior change. This in turn affects the approach to education, suggesting that since more success is associated with more extrinsic rather than intrinsic benefits, more effective approaches to public education need to be less didactic.

High amounts of food waste combined with the globally rising population rate is exacerbating the global food supply, while simultaneously, solid waste generation is increasing faster than any other environmental pollutant, including CO2. These factors combined are creating a major crisis throughout the world, including in developed as well as developing countries. The compulsory food waste system of the South Korean government offers a creative solution to this global problem. This incentive-based solution to food waste in an industrialized country offers a blueprint which can be replicated by other governments as the demand to reduce food waste grows bigger, presenting a serious threat to the planet.

As the world continues to focus on achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals agreed upon in the year 2015, and as the world looks to recover from the devastating impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, South Korea’s food waste program offers a solution for how countries can significantly contribute to meeting Sustainable Development Goal 2 to achieve zero hunger by 2030. The model the South Korean government laid out positively impacts SDG 12, in meeting sustainable consumption and production through promoting more sustainable lifestyles by reducing individual food waste, thereby surpassing SDG 12.3 “Food Waste Index” that targets the per capita global food waste to be reduced by half at both the retail and consumer levels by 2030.

With food waste and food loss being a global problem across the food system from production to consumption, reducing food waste and loss is a key measure for the world to meet the necessary reduction in greenhouse gas emissions for a more sustainable future, as well as to aid recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, and adopt new approaches that create heathier individuals and societies.

References

2020 - Global Report on Food Crises. (2020). https://www.wfp.org/publications/2020-global-report-food-crises

Aschemann-Witzel, J., Hooge, I. D., Amani, P., Bech-Larsen, T., & Oostindjer, M. (2015). Consumer-Related Food Waste: Causes and Potential for Action. Sustainability, 7(6), 6457-6477. doi:10.3390/su7066457

Aschemann-Witzel, J., Hooge, I. D., & Normann, A. (2016). Consumer-Related Food Waste: Role of Food Marketing and Retailers and Potential for Action. Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing, 28(3), 271-285. doi:10.1080/08974438.2015.1110549

Bravi, L., Murmura, F., Savelli, E., & Viganò, E. (2019). Motivations and Actions to Prevent Food Waste among Young Italian Consumers. Sustainability, 11(4), 1110. doi: 10.3390/su11041110

Broom, D. (2019, April 12). South Korea once recycled 2% of its food waste. Now it recycles 95%. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/04/south-korea-recycling-food-waste/

Barclay, E., & Irfan, U. (2019, November 26). 10 ways to accelerate progress against climate change. https://www.vox.com/2018/10/10/17952334/climate-change-global-warming-un-ipcc-report-solutions-carbon-tax-electric-vehicles

Duhaime, A. (2017, March 17). Our Brains Love New Stuff, and It's Killing the Planet. https://hbr.org/2017/03/our-brains-love-new-stuff-and-its-killing-the-planet

EC, JRC/PBL, 2012 Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research, version 4.2.

Fight climate change by preventing food waste. (n.d.). https://www.worldwildlife.org/stories/fight-climate-change-by-preventing-food-waste

Galford, G. L., Peña, O., Sullivan, A. K., Nash, J., Gurwick, N., Pirolli, G., . . . Wollenberg, E. (2020). Agricultural development addresses food loss and waste while reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Science of The Total Environment, 699, 134318. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134318

Goal 2: Zero Hunger – United Nations Sustainable Development. (n.d.). https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/hunger/

Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production – United Nations Sustainable Development. (n.d.). https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production/

Goal 13: Climate Action – United Nations Sustainable Development. (n.d.). https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/climate-change/

Goal 14: Life Below Water – United Nations Sustainable Development. (n.d.). https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/oceans/

Goal 15: Life On Land – United Nations Sustainable Development. (n.d.). https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/biodiversity/

Gunders, D. (2012, August). Wasted: How America is losing up to 40 percent of its food from farm to fork to landfill. Natural Resources Defense Council website. http://www.nrdc.org/food/files/wasted-food-ip.pdf

Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U.; Van Otterdijk, R.; Meybeck, A. Global Food Losses and Food Waste; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Taly, 201l. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i2697e.pdf

Hingston, S. T., & Noseworthy, T. J. (2020). On the epidemic of food waste: Idealized prototypes and the aversion to misshapen fruits and vegetables. Food Quality and Preference, 86, 103999. doi:10.1016/j.foodqual.2020.103999

Hurlock, E. B. (1931). The Psychology of Incentives. The Journal of Social Psychology, 2(3), 261-290. doi:10.1080/00224545.1931.9918976

Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Rewards to Improve Employee Engagement. (2019, April 16). https://www.bravowell.com/resources/intrinsic-vs.-extrinsic-rewards-to-improve-employee-engagement

Kool, W., Mcguire, J. T., Rosen, Z. B., & Botvinick, M. M. (2010). Decision making and the avoidance of cognitive demand. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 139(4), 665-682. doi:10.1037/a0020198

Kuriansky, J. (2021). COVID-19, Food Security & Mental Health in the context of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Presentation at online webinar, United Nations Commission on Population and Development, sponsored by the US Federation of UNESCO Clubs, April 22.

Lombrozo, T. (2015, November 30). How Psychology Can Save The World From Climate Change. https://www.npr.org/sections/13.7/2015/11/30/457835780/how-psychology-can-save-the-world-from-climate-change

Martin, M., Maddocks, E., Chen, Y., Gilman, S., & Colman, I. (2016). Food insecurity and mental illness: Disproportionate impacts in the context of perceived stress and social isolation. Public Health, 132, 86-91. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2015.11.014

Nemeth, D., Hamilton, R. & Kuriansky, J. (2015). Reflections and Recommendations: The Need for Leadership, Holistic Thinking, and Community Involvement. In Nemeth, D.G. & Kuriansky, J. (Eds., Volume 11: Interventions and Policy). Ecopsychology: Advances in the Intersection of Psychology and Environmental Protection. pp. 419-424. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO/Praeger.

Newman, D., & Cepeda-Márquez Ricardo. (2018). Global Food Waste Management: An Implementation Guide for Cities. World Biogas Association.

Oceans – United Nations Sustainable Development. (n.d.). https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/oceans/

Pearson D., Minehan M., Wakefield-Rann R. Food waste in Australian households: Why does it occur. Aust. Pac. J. Reg. Food Stud. 2013;3:118–132.

Pourmotabbed, A., Moradi, S., Babaei, A., Ghavami, A., Mohammadi, H., Jalili, C., . . . Miraghajani, M. (2020). Food insecurity and mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutrition, 23(10), 1778-1790. doi:10.1017/s136898001900435x

Risk of hunger pandemic as coronavirus set to almost double acute hunger by end of 2020: World Food Programme. (n.d.). https://www.wfp.org/stories/risk-hunger-pandemic-coronavirus-set-almost-double-acute-hunger-end-2020

Reducing the Impact of Wasted Food by Feeding the Soil and Composting. (2020, October 29). https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/reducing-impact-wasted-food-feeding-soil-and-composting

Sengupta, S. (2017, December 12). How Much Food Do We Waste? Probably More Than You Think. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/12/climate/food-waste-emissions.html

SDG 12.3 Food waste index. (n.d.). https://www.unep.org/thinkeatsave/about/sdg-123-food-waste-index

Sustainable Development Goals. (n.d.). https://www.who.int/health-topics/sustainable-development-goals#tab=tab_1

Sustainable Management of Food Basics. (2021, January 13). https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/sustainable-management-food-basics

Swim, J. K., Stern, P. C., Doherty, T. J., Clayton, S., Reser, J. P., Weber, E. U., . . . Howard, G. S. (2011). Psychology's contributions to understanding and addressing global climate change. American Psychologist, 66(4), 241-250. doi:10.1037/a0023220

Thyberg, K. L., & Tonjes, D. J. (2016). Drivers of food waste and their implications for sustainable policy development. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 106, 110-123. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.11.016

UN Environment Programme. (n.d.). Minimizing food waste. https://www.unep.org/regions/north-america/regional-initiatives/minimizing-food-waste#:~:text=Globally, if food waste could,3.3 billion tons of CO2.

Water in Agriculture. (2020, May 8). https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/water-in-agriculture

Zero Waste Declaration. (n.d.). https://www.c40.org/other/zero-waste-declaration

Reported by Shelby Parks, a member of the Student Division of he International Association of Applied Psychology,has an M.A. degree in Psychology and Education in the Department of Clinical and Counseling Psychology, Columbia University Teachers College, where she was a student in Professo rDr. Judy Kuriansky’s class on “Psychology and the United Nations.” Shelby is also a writer and speaker on the psychology of climate change and has given presentations and formed partnerships with Columbia University, AARP, ViacomCBS, and Ecoversity.

Cite this article as: Parks, S. A. (2021). Food Waste Mitigation in Industrialized Countries: The Problem and Model Solutions to Achieve Sustainable Development, Well-being and Eradication of Hunger through Behavior Science featuring the Case of South Korea. International Association of Applied Psychology: IAAP at the United Nations. https://iaapsy.org/iaap-and-the-united-nations/reports-meetings-events/food-waste-mitigation-achieving-sustainable-development-well-being-and-hunger-eradication-applying-behavior-science-in-the/